The myth of the Trojan War and its legacy in art and literature in the BP exhibition Troy: myth and reality from 21 November 2019 – 8 March 2020. Troy is famous ancient city in what is now northwestern Turkey, made famous in Homer's epic poem, the Iliad.

The story of the ancient city of Troy, and of the great war that was fought over it, has been told for some 3,000 years.

Troy was a city in the far northwest of the region known in late Classical antiquity as Asia Minor, now known as Anatolia in modern Turkey.

Spread by travelling storytellers, it was cast into powerful words by the Greek poet Homer as early as the eighth to seventh century BC – and into powerful images by ancient Greek and Roman artists. Just as it enraptured audiences in the past, it still speaks to us today and it’s easy to see why. It’s a story that has it all – love and loss, courage and passion, violence and vengeance, triumph and tragedy – on a truly epic scale.

Spanning several decades, the tale is set in Greece’s mythical past. At its heart is the powerful city of Troy on the western coast of Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), besieged for 10 years by the Greeks, who sailed across the Aegean Sea to take revenge for a grave insult – the abduction of a woman. This ancient world war features a stellar cast of characters. Even the gods are involved.

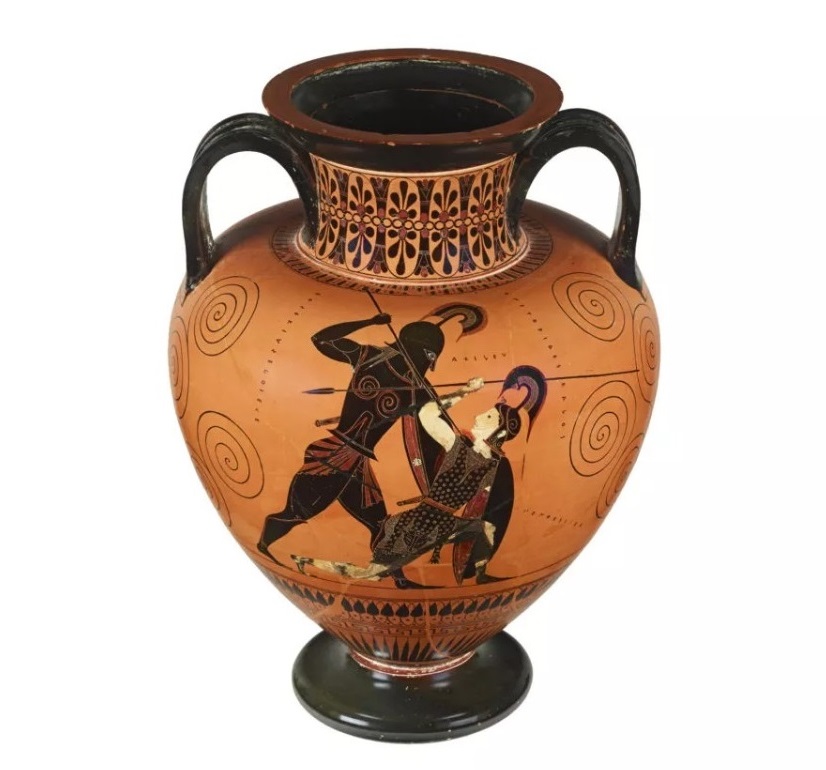

The Greek hero Achilles kills the Amazon queen Penthesilea, fighting on the Trojan side, on a black-figure amphora from c. 530BC. According to one version of the story, at the very moment of her death, their eyes meet and he falls in love with her [Credit: Trustees of the British Museum]

But this isn’t a straightforward tale of right and wrong. Its heroes – and none more so than the great Achilles – are complex, with heroic strength but human weaknesses and in the end it is unclear who, if anyone, really wins.

Judgement of Paris

The story starts with a wedding. The sea-goddess Thetis is marrying a mortal man and all the gods and goddesses are invited except one – Eris, the goddess of discord. Angered, she throws a golden apple into the party, bearing the inscription ‘to the most beautiful’.

This Etruscan tomb-painting shows the Judgement of Paris. At the left, Paris awaits the three goddesses. Aphrodite, last of the three, lifts her dress to show off a flash of leg. On the right, Helen is approached by three women bringing jewellery and perfume [Credit: Trustees of the British Museum]

Three goddesses all claim it for themselves, and the king of the gods, Zeus, not willing to get involved himself, picks the Trojan prince Paris as the judge. The goddess of love, Aphrodite, wins the competition as she has promised Paris possession of the most beautiful women on earth, Helen. There’s just one problem. Helen is already married to Menelaus, king of the Greek city of Sparta.

The face that launched a thousand ships

Paris, prince of Troy, comes to Sparta on a state visit but, outrageously, leaves with his host’s wife Helen, queen of Sparta. To bring Helen back and restore his honour, the deceived husband, King Menelaus, assembles a huge army of Greek heroes. Its leader is Menelaus’ brother Agamemnon, king of the powerful Greek city of Mycenae.

Some think Paris abducted Helen, others say she fell in love and followed him willingly. The South Italian artist of this vessel suggests the blame lies with the gods. Aphrodite stands directly behind Helen, who is lifting her veil to Paris for the first time. Below, Eros playfully allows a dog to chase a goose, perhaps suggesting infatuated humans are just a plaything of the gods [Credit: Trustees of the British Museum]

The army sails to Troy, sets up camp and lays siege to the city. But Troy has strong walls and the Trojans defend the city bravely, throughout nine long years of fighting. The Greeks succeed, however, in raiding neighbouring Trojan cities, taking some inhabitants as prisoners. Among them is Briseis, a young woman who is given to Greek hero Achilles as a prize of honour.

The rage of Achilles

In the 10th year of the Trojan War, dramatic events unfold, as told in Homer’s Iliad. King Agamemnon, the leader of the Greek forces, seizes Briseis for himself. Furious, Achilles withdraws from battle, together with his troops. Achilles’ mother, the sea goddess Thetis, asks Zeus to favour the Trojans for a while, so that Agamemnon will regret dishonouring her son.

On this Athenian drinking cup Achilles sits withdrawn and angry inside his tent, heavily wrapped in his cloak, as two heralds lead away his prize, the enslaved woman Briseis [Credit: Trustees of the British Museum]

In the fighting that follows, the Trojans gain ground and are able to set up camp on the plain, alarmingly close to the Greek ships. Desperate to drive them back, Achilles’ close friend and perhaps lover, Patroclus, disguises himself in the armour of Achilles and leads the Greeks into battle, hoping to raise Greek morale and intimidate the Trojans. At first the plan works, but Patroclus is killed by the Trojan prince Hector. In a state of grief-stricken rage, desperate for vengeance against Hector, Achilles sets aside his quarrel with Agamemnon.

The death of Hector

Achilles returns to battle, wearing new armour brought by his mother. Victory once more favours the Greeks – and Achilles succeeds in killing Hector.

Achilles and Hector face each other in combat. Achilles lunges forward while Hector falls back, his wounded chest exposed [Credit: Trustees of the British Museum]

Consumed by rage and grief, he does not allow Hector’s body to be reclaimed by the Trojans for the customary funeral. Instead he desecrates it by dragging it behind his chariot, as Hector’s horrified family watch from the walls of Troy. Over the coming days he repeatedly drags the body in the dust. But the gods take pity on Hector and his family, preserving Hector’s body from damage and decay. The messenger god, Hermes, helps Hector’s distraught father, Trojan King Priam, to enter the Greek camp secretly. He begs Achilles for the ransom of his son’s body.

Trojan King Priam kisses the hand of Achilles, the man who killed his son. This exquisite Roman silver cup was found in a chieftain’s grave in Denmark [Credit: Roberto Fortuna and Kira Ursem © National Museet Denmark]

Achilles’ pitiless need for vengeance subsides and he agrees to Priam’s request. It is an extraordinary, moving encounter, which restores humanity to the hero and a sense of order to the world. The funeral of Hector can now take place. This point in the story is where the Iliad ends.

The death of Achilles

Hector is dead, but the war goes on. Troy has not yet fallen and more allies come to the city’s aid, some from far afield. With the help of Achilles, the Greeks defeat both the Amazons (female warriors led by their queen Penthesilea) and the Ethiopians under King Memnon. But Achilles knows that he is fated to die young, for his divine mother once foretold that he would have a short life if he stayed to fight at Troy.

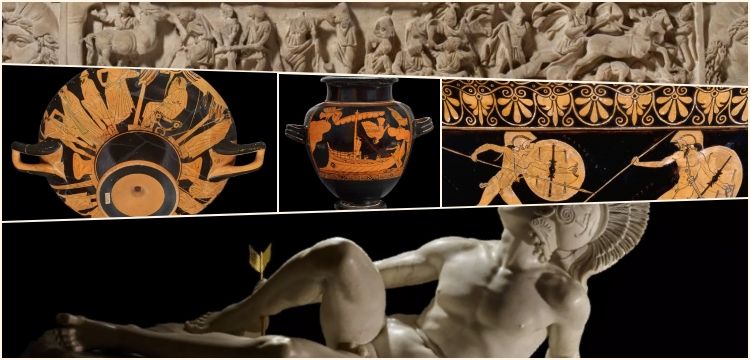

In this neoclassical marble sculpture, Wounded Achilles, by Filippo Albacini (1777–1858), which was commissioned for the sculpture gallery at Chatsworth House, Achilles grips the arrow which has pierced his heel [Credit: © The Devonshire Collections, Chatsworth]

It is Paris, the Trojan prince whose abduction of Helen started the war, who kills Achilles. According to one version of the story, Achilles’ divine mother tried to make him invulnerable to injury as a baby, dipping him into the waters of the river Styx. But she held him by one heel – the famous Achilles’ heel – and this is the weak point where Paris hits him with an arrow, finally felling the great warrior.

The fall of Troy

The Greeks finally win the war by an ingenious piece of deception dreamed up by the hero and king of Ithaca, Odysseus – famous for his cunning. They build a huge wooden horse and leave it outside the gates of Troy, as an offering to the gods, while they pretend to give up battle and sail away.

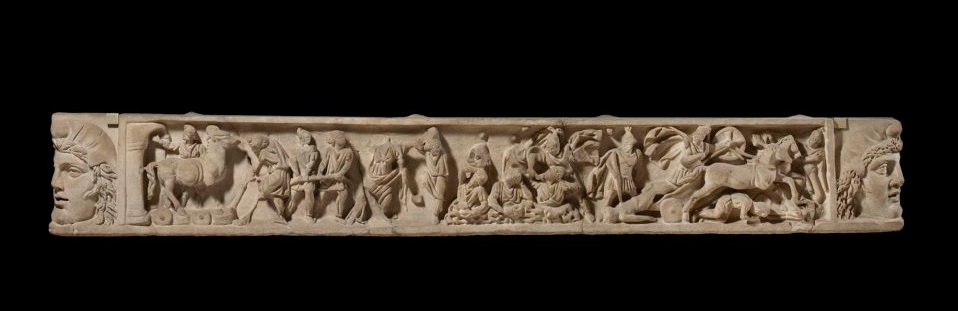

Roman sarcophagus lid, late 2nd century AD [Credit: © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford]

Secretly, though, they have assembled their best warriors inside. The Trojans fall for the trick, bring the horse into the city and celebrate their victory. But when night falls, the hidden Greeks creep out and open the gates to the rest of the army, which has sailed silently back to Troy.

On this detail of the Roman sarcophagus lid, the wooden horse is being pulled into the city. The splendid wheeled horse is itself armed with helmet and shield – a suggestion of the warriors hiding within [Credit: © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford]

The city is sacked, the men and boys are brutally slain, including King Priam and Hector’s little son Astyanax, and the women are taken captive. Troy has fallen. But there is still hope for the Trojans’ survival – Aeneas, the son of King Priam’s cousin, escapes the city with his old father, his young son and a band of Trojan refugees. Aeneas’ story is told in Virgil’s Aeneid.

Returning home

After the fall of Troy, the surviving heroes and their troops have little chance to enjoy their victory. The gods are angry because many Greeks committed sacrilegious atrocities during the sacking of Troy. Few Greeks reach their homes easily, or live to enjoy their return. The most difficult, lengthy and action-packed journey is that of Odysseus as told in Homer’s Odyssey. He is forced to travel to the furthest reaches of the Mediterranean Sea, tormented by the sea god Poseidon.

Wily Odysseus finds a way to hear the Sirens’ beautiful, all-knowing song, without being lured to his death on the dangerous cliffs below. He has his men tie him to the mast of the ship and then seal their own ears with wax so they can row on, immune to the bird women’s irresistible singing [Credit: Trustees of the British Museum]

He is waylaid by storms, shipwreck and a colourful crowd of strange beings and treacherous people, from the one-eyed giant Cyclops to the Sirens with their mesmerising song. Odysseus finally reaches his homeland, only to find his house besieged by suitors for the hand of his wife who had thought he would not survive his voyage. Yet after 10 years at sea, Odysseus also overcomes this final challenge. He kills the suitors and is reunited with his faithful wife, Penelope.

With Odysseus home at last, the events of the Trojan War come to a close. Whether Greek or Trojan, victorious or defeated, the heroes and heroines of the story have enthralled audiences from antiquity to today.

Find out more about Troy, the myth of the Trojan War and its legacy in art and literature in the BP exhibition Troy: myth and reality from 21 November 2019 – 8 March 2020.

Source: Victoria Donnellan - British Museum [June 30, 2019]

Roma dönemine ait 3500 yıllık sütunlu cadde mi keşfedildi, güldürmeyin insanı!

Roma dönemine ait 3500 yıllık sütunlu cadde mi keşfedildi, güldürmeyin insanı!  Merhum seramik Sanatçısı Melike Abasıyanık Kurtiç'in eserleri Bir Denizkestanesinin Anıları'nda

Merhum seramik Sanatçısı Melike Abasıyanık Kurtiç'in eserleri Bir Denizkestanesinin Anıları'nda  Kayıp Şehirlerin gizemli çağrısı: Arkeolojik keşiflerin yolunu açan efsaneler

Kayıp Şehirlerin gizemli çağrısı: Arkeolojik keşiflerin yolunu açan efsaneler  Sebastapolis Antik Kenti, Tokat'taki depremleri hasarsız atlattı

Sebastapolis Antik Kenti, Tokat'taki depremleri hasarsız atlattı